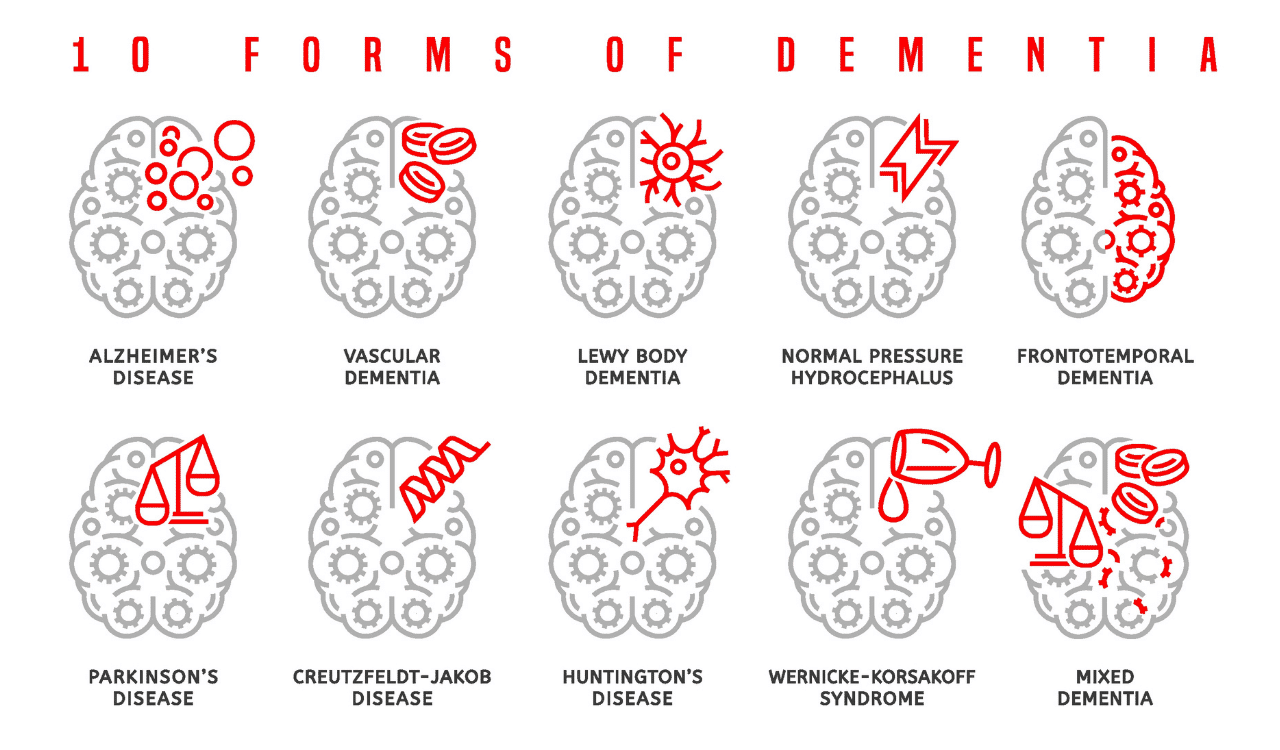

10 Kinds of Dementia

Demystifying Dementia

The term “dementia” often conjures images of memory loss, but it represents a far more complex and diverse spectrum of cognitive decline. It’s a progressive syndrome that impacts not just memory but also thinking, behavior, and the ability to perform daily activities. Globally, over 55 million people were living with dementia in 2021, a figure projected to rise significantly, with over 60% living in low- and middle-income countries [World Health Organization, 2025]. This increasing prevalence underscores the urgent need for comprehensive information that can empower individuals and communities to confront this condition. This article aims to provide that clarity, detailing the distinct pathways dementia can take, from the most common forms to rarer but equally significant conditions.

What is Dementia? (Beyond just memory loss; a syndrome of cognitive decline affecting daily life)

Dementia is not a single disease but rather an umbrella term for a group of symptoms characterized by a significant decline in cognitive function that interferes with daily life. These symptoms go beyond typical age-related forgetfulness and can include difficulties with memory, reasoning, language, problem-solving, and visual perception.

These problems usually include serious memory loss. They can also include trouble with language, planning, decision-making, visual-spatial skills, and judgment. The underlying cause is damage to or loss of brain cells and their connections in the brain. This damage disrupts communication between brain cells and can affect different areas of the brain depending on the type of dementia, leading to a wide array of manifestations. Ultimately, dementia affects a person’s ability to function independently, impacting their social interactions, work, and personal care.

Dementia vs. Normal Aging (Distinguishing significant cognitive impairment from age-related changes)

It is common for individuals to experience subtle changes in cognition as they age. This can include occasional forgetfulness, such as misplacing keys or struggling to recall a name. Normal aging may slow thinking or reduce multitasking ability. But it usually does not stop a person from managing money, having conversations, or moving around familiar places.

However, dementia represents a far more profound and pervasive cognitive decline. In contrast, dementia-related cognitive impairment is severe enough to disrupt these everyday activities. For instance, while an older adult might forget where they put their glasses, someone with dementia might forget the purpose of glasses or how to use them. Distinguishing between these is critical for timely diagnosis and appropriate management.

Why Understanding Different Types Matters (Impact on symptoms, prognosis, treatment approaches, and research)

Recognizing that dementia encompasses a variety of conditions is paramount. Each type of dementia has a unique underlying pathology, affecting different parts of the brain and presenting with distinct symptoms. This differentiation is crucial for several reasons:

- Symptom Variation: The specific symptoms experienced, their onset, and their progression vary significantly. For example, Alzheimer’s disease primarily impacts memory, while Frontotemporal Dementia often affects personality and behavior.

- Prognosis: The anticipated course and duration of the illness differ among dementia types. Some progress more rapidly than others.

- Treatment and Management: While there is no cure for most dementias now, medical treatments, lifestyle changes, and strong support can improve life for people with dementia and their caregivers. Specific medications and management strategies can help alleviate certain symptoms or slow their progression, but these are often type-specific.

- Research Focus: Understanding the distinct biological underpinnings of each dementia type is essential for developing targeted research efforts and potential future treatments or cures.

The Core Elements of Dementia: Symptoms, Causes & Brain Changes

At its heart, dementia is a consequence of damage to the brain. This damage can arise from a variety of processes that disrupt the normal functioning of brain cells and their intricate network. Key to understanding dementia is recognizing that it’s not a singular entity but a syndrome with multiple potential origins, each leading to a cascade of cognitive and behavioral changes.

Dementia mainly causes cognitive decline, including memory loss and problems with language, planning, visual skills, and judgment. These issues happen because parts of the brain are damaged. For example, poor blood flow from heart problems or stroke can cause vascular dementia. Diseases like Alzheimer’s involve harmful protein buildup that kills brain cells. Parkinson’s disease can also cause dementia through Lewy bodies, abnormal protein deposits. Identifying symptoms and understanding brain damage helps diagnose the dementia type.

The Most Common Types of Dementia

While numerous conditions can lead to cognitive impairment, several types of dementia are far more prevalent. Understanding these common forms is essential for recognizing potential signs and seeking appropriate guidance.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

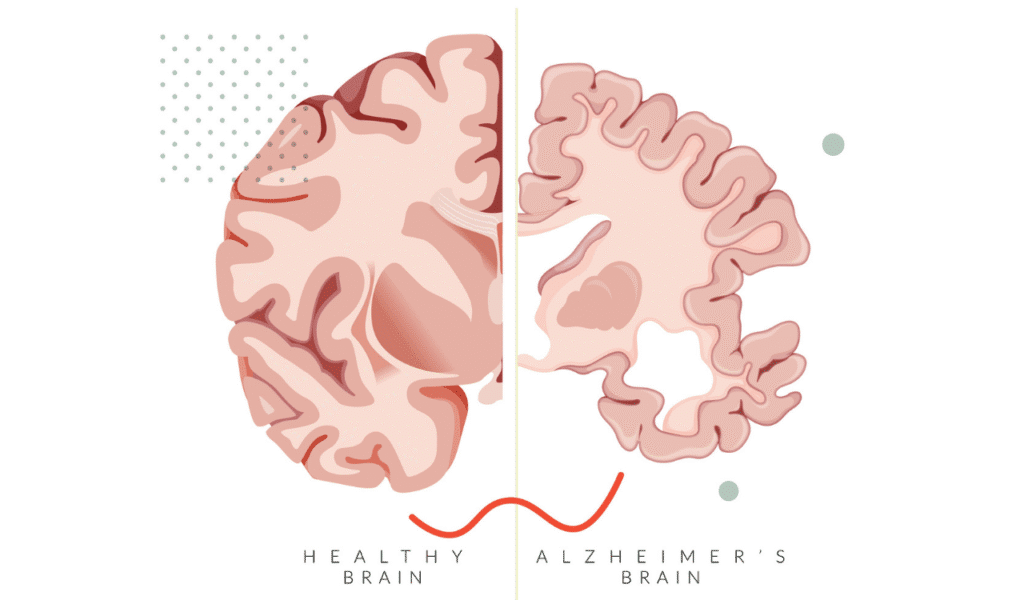

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for an estimated 7.2 million Americans age 65 and older in 2025 [Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, 2025]. It is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the gradual accumulation of abnormal protein deposits, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (composed of tau protein), in the brain cells.

These proteins disrupt brain cells function, leading to brain cell death and a shrinking of the brain over time, particularly in areas vital for memory and thinking, such as the entorhinal cortex. The hallmarksymptoms of Alzheimer’s disease typically begin with subtle memory loss, especially difficulty recalling recent events or newly learned information.

As the disease progresses, memory deficits become more severe, and other cognitive functions are affected, including language (finding the right words), reasoning, and judgment. Familial Alzheimer’s disease is a rarer form that is inherited, and genetic testing can identify mutations in genes like Apolipoprotein E.

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia and arises from conditions that damage blood flow to the brain. This damage can occur due to a stroke (a sudden interruption of blood flow causing brain cell death) or a series of smaller small strokes, or from chronic conditions that narrow and block blood flow to the brain, such as cerebral atherosclerosis. This can lead to Multi-infarct dementia or subcortical vascular dementia, where damage occurs in smaller blood vessels deeper within the brain tissue. When brain cells are deprived of oxygen and nutrients, they can die, leading to cognitive impairment.

The symptoms of vascular dementia can appear suddenly after a stroke or develop gradually over time as blood flow is progressively restricted. They often depend on the location and extent of the brain damage. Common symptoms include problems with planning, organizing, decision-making, and reasoning (executive function), as well as slower thinking and difficulty with problem-solving.

Lewy Body Dementias: Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD)

Lewy body dementias represent a group of conditions characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies, which are abnormal clumps of the protein alpha-synuclein that develop inside brain cells in the brain. These deposits disrupt normal brain cell functioning and can lead to a variety of cognitive, motor, and behavioral symptoms. This category includes two closely related conditions: Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s Disease Dementia (PDD). Together, they account for a significant percentage of dementia cases, estimated at 5-10%.

Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) typically presents with cognitive symptoms that appear either before or at the same time as significant motor symptoms (like those seen in Parkinson’s disease). Core symptoms of DLB include recurrent visual hallucinations (seeing things that aren’t there), fluctuations in alertness and attention, and Parkinsonian motor symptoms such as tremors, rigidity, and slowness of movement. Sleep disturbances, particularly acting out dreams, are also common.

Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) occurs in individuals who have already been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and later develop dementia. In PDD, the Parkinsonian motor symptoms typically appear at least a year before the onset of dementia. The underlying pathology and many symptoms overlap with DLB, highlighting the close relationship between these Lewy body diseases.

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) is a group of less common neurodegenerative disorders that primarily affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. These areas are responsible for personality, behavior, language, and executive functions. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, memory loss is often not the predominant early symptom in FTD. Instead, FTD typically manifests as significant changes in personality, behavior, and/or language.

There are several subtypes of FTD, with the most common being behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD). Individuals with bvFTD may exhibit profound changes in personality and behavior, such as a loss of empathy, compulsive behaviors, apathy, disinhibited behaviours, or changes in eating habits. Other forms of FTD include primary progressive aphasia (PPA), which primarily affects language abilities, and Pick’s Disease, which is characterized by specific pathological changes within these lobes, including the presence of Pick bodies.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Corticobasal degeneration are also considered part of the broader spectrum of Frontotemporal disorders, often presenting with prominent motor symptoms alongside cognitive and behavioral changes. The pathology often involves abnormal accumulations of tau protein or TDP-43 protein (Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy).

Less Common, Yet Important, Types of Dementia

Beyond the most prevalent forms, several other conditions can lead to dementia, each with its unique causes and characteristic symptoms. Recognizing these less common types is vital for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH) is a neurological condition characterized by a triad of symptoms: gait disturbance (difficulty walking, often described as shuffling), urinary incontinence, and cognitive impairment, including problems with memory and reasoning. It occurs when cerebrospinal fluid accumulates in the brain’s ventricles, increasing pressure and damaging surrounding brain cells, but without a significant increase in overall head size. Crucially, NPH is potentially treatable; a surgical procedure to implant a shunt to drain the excess fluid can sometimes reverse or significantly improve the symptoms. This contrasts with many other forms of dementia where progression is inevitable.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) is a rare, rapidly progressive, and fatal neurodegenerative disease caused by abnormal proteins called prions. These prions cause healthy proteins in the brain to fold incorrectly, leading to widespread damage and loss of brain cells. The symptoms of CJD typically appear quickly and worsen rapidly over weeks or months, including dementia, memory loss, behavioral changes, coordination problems, and muscle stiffness. Its rapid progression, often within a year or two, distinguishes it from many other forms of dementia.

Huntington’s Disease

Huntington’s Disease (HD) is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by a genetic mutation that leads to the progressive breakdown of brain cells in the brain. It affects motor control, cognition, and psychiatric state. The motor symptoms typically include involuntary movements (chorea), muscle rigidity, and problems with balance and coordination.

Cognitive decline can manifest as difficulties with planning, organizing, focusing, and memory. Psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and irritability, are also common. The progressive degeneration of brain cells in specific areas, particularly the basal ganglia and cortex, underlies the multifaceted symptoms of Huntington’s Disease. The cause is a mutation in the gene that produces the protein ‘huntingtin’.

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome is a serious brain disorder. It happens when the body lacks thiamine (vitamin B1). It often occurs with long-term alcohol-related brain injury, but can also happen with severe malnutrition or medical problems that stop nutrient absorption. The condition has two stages:

Wernicke’s encephalopathy (acute) and Korsakoff’s psychosis (chronic). Wernicke’s encephalopathy can cause confusion, loss of muscle coordination, and vision problems. If not treated, it can lead to Korsakoff’s psychosis. This causes serious memory problems. People cannot form new memories. They may make up stories to fill memory gaps. They also may show lack of interest. Damage to specific brain cells and pathways, especially in areas related to memory, causes these debilitating symptoms. This condition is also known as Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome.

HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND)

HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND) refers to a range of cognitive impairments that can occur in people living with HIV infection. The virus itself, and the chronic inflammation it causes, can affect brain cells, leading to difficulties with attention, memory, processing speed, and motor skills. While highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly reduced the incidence and severity of HAND, it can still occur, particularly in individuals with uncontrolled HIV or long-standing infection. The symptoms can vary from mild cognitive motor disorder to a more severe dementia-like condition.

Other Notable Dementias (Brief Mentions)

Beyond these types, other conditions can contribute to cognitive decline and dementia. These include dementia resulting from brain injury (such as Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), often linked to repetitive head trauma, including Blast-induced traumatic brain injury), brain infections, certain autoimmune disorders, and exposure to toxins. While not always classified strictly as “dementia” in the same way as Alzheimer’s, conditions like multiple sclerosis can also present with significant cognitive impairment due to damage to brain tissue. Each of these has specific causes and potential treatment pathways, highlighting the diverse origins of cognitive impairment.

The Diagnostic Process: How Dementia is Identified

Diagnosing dementia is a multi-faceted process that involves careful evaluation by healthcare professionals. It’s crucial to identify the specific type of dementia, as this influences prognosis and treatment strategies. In 2022, 4.0% of adults age 65 and older in the United States reported ever having received a dementia diagnosis [CDC, 2024]. This figure underscores the importance of understanding the diagnostic journey.

Initial Assessment and Medical History (Reviewing symptoms, onset, progression, family history, and ruling out other conditions)

The diagnostic process typically begins with a comprehensive medical history and physical examination. Healthcare providers will gather detailed information about the individual’s symptoms, including when they started, how they have progressed, and their impact on daily life. They will inquire about family history, as some types of dementia have a genetic component.

Crucially, the physician will also ask about other medical conditions, medications, lifestyle factors, and potential depression, as these can sometimes mimic or contribute to cognitive decline. This thorough review helps the clinician begin to differentiate dementia from other conditions and narrow down the possibilities for its underlying cause.

After the first check, tests like the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) assess memory, attention, language, and problem-solving. Neuropsychological tests give detailed views of cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Brain scans (MRI scan or CT) show structural changes like shrinkage or stroke signs.

Blood tests rule out reversible causes like vitamin deficiencies or infections. Sometimes, cerebrospinal fluid analysis or positron emission tomography (PET) and SPECT PET scans confirm or distinguish dementia types. Brain imaging tests provide valuable clues, and in some cases, brain tissue analysis after death can definitively confirm the type of dementia.

Is It Always Dementia? Reversible Causes of Cognitive Decline

It is critically important to understand that not all cognitive decline is due to irreversible dementia. Many conditions can mimic the symptoms of dementia, but are treatable and potentially reversible. These include:

- Medication Side Effects: Numerous prescription and over-the-counter medications can cause confusion, memory problems, or difficulty concentrating.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: A lack of essential vitamins, particularly vitamin B12, can lead to cognitive impairment.

- Thyroid Problems: An underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) can slow down metabolism and affect cognitive function.

- Infections: Urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and other systemic infections can cause delirium, which presents with sudden confusion and cognitive changes.

- Depression: Significant depression can lead to apathy, difficulty concentrating, and memory problems, mimicking dementia.

- Alcohol-Related Brain Injury: Chronic excessive alcohol consumption can lead to conditions like Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome, which can cause severe cognitive impairment.

Living with a Dementia Diagnosis: Management and Support

Receiving a dementia diagnosis can be overwhelming, but it is the first step toward effective management and accessing crucial support. While currently incurable, a combination of medical interventions, lifestyle adjustments, and a robust support network can significantly enhance the quality of life for individuals living with dementia and their caregivers. Researchers estimate a lifetime risk of dementia of 42% after age 55 [National Institutes of Health, 2025], underscoring the widespread impact.

Management strategies are tailored to the specific type of dementia. For example, medications like acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (also known as anticholinesterase inhibitors) can help manage symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementias by affecting neurotransmitter levels in the brain. For vascular dementia, managing underlying cardiovascular risk factors like high blood pressure and cholesterol is paramount to prevent further blood flow damage.

Doing stimulating activities and living a healthy life can help. Making a safe and familiar environment also helps. These steps can help people manage symptoms and stay independent longer. Approaches like cognitive training, assistive technology, and digital health tools can support daily living. Support groups offer invaluable emotional and practical assistance for both individuals with dementia and their families. Person-centered care, which focuses on the individual’s needs and preferences, is essential in all care settings, including long-term care facilities.

The Role of Research (Ongoing efforts to understand causes, develop new treatments, and find cures for various types of dementia)

The landscape of dementia research is dynamic and hopeful. Scientists worldwide are working tirelessly to unravel the complex mechanisms behind various forms of dementia, seeking to develop more effective treatments and ultimately, cures. For Alzheimer’s disease, research is focused on clearing amyloid plaques and tau tangles, exploring neuroinflammation, and identifying genetic factors.

In vascular dementia, research aims to better understand the impact of blood flow disruptions and develop strategies to protect the brain from stroke damage. For Lewy body dementias, investigators are studying alpha-synuclein aggregation and its toxic effects on brain cells. Frontotemporal Dementia research is delving into the specific protein pathologies and genetic underpinnings of its diverse subtypes.

Advancements in brain imaging scans, genetic testing, and brain tissue analysis are providing deeper insights into the progression of these conditions. The ultimate goal of this research is to prevent, slow, or even reverse the brain changes that lead to dementia, offering hope for a future where these conditions are more effectively managed or eradicated.

Conclusion: Navigating the Complex Landscape of Dementia

Dementia is a complex and multifaceted syndrome, not a single disease. As explored, its various forms, from the common Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia to Lewy body dementias and Frontotemporal Dementia, each present unique challenges stemming from distinct brain changes and pathological processes. Understanding these differences in symptoms, causes, and progression is the bedrock of accurate diagnosis and effective management. It is crucial to differentiate dementia from reversible causes of cognitive decline, a task that necessitates thorough medical evaluation.

Key Takeaways (Reiterating the diversity of dementia types, the importance of accurate diagnosis, and the multifaceted nature of care)

The journey with dementia is deeply personal and varies greatly depending on the underlying type. Key takeaways to remember include:

- Diversity of Types: Dementia is an umbrella term encompassing numerous conditions affecting the brain, each with distinct characteristics, from Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia to Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Frontotemporal Dementia, Huntington’s Disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Korsakoff Syndrome, among others.

- Importance of Diagnosis: An accurate diagnosis of the specific dementia type is critical for guiding treatment, predicting prognosis, and accessing appropriate support. Distinguishing between conditions like Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease dementia, or identifying treatable conditions like Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus, can significantly alter outcomes.

- Multifaceted Care: Living with dementia requires a comprehensive approach involving medical support (including medications like anticholinesterase inhibitors), therapeutic interventions (like cognitive training), lifestyle adjustments, and robust emotional and practical assistance for both the individual and their caregivers.

- Hope in Research: Ongoing research continues to illuminate the complexities of dementia, offering hope for improved treatments and a better understanding of brain cell death, protein pathologies (amyloid plaques, tau protein), blood flow issues, and genetic factors.

Leave a Reply